About me

Welcome to my personal website!

Can docstring reformulation with an LLM improve code generation?

This post is the second of a series that looks back at my works during the PhD, to reflect on what I wanted to do, the background story of the paper, what was promising, what were the biggest limitations of the project and overall what I learned.

Paper link: Can docstring reformulation with an LLM improve code generation?

Background

In January 2023, after the first submission of my first paper, I started thinking about what to do next. I had spent 2 full years out of 4 that I had funding for on my first paper, and the unspoken rule at my department was that one needed 4 papers to finish the PhD, so clearly I felt a lot of pressure on my shoulders for publishing. An obvious idea from my supervisor and advisor was that I should extend my work with a second paper on the language-instructed model-based RL architecture of my first paper, yet I opposed myself to that, because I knew that I had hated the experience of that work and I needed something new to work on. Also, I had seen up close the shortcomings of the work, so I was not willing to build up on that.

At the same time, a revolution was starting to take place in the field: a little more than a month earlier ChatGPT was released, cool works such as “Code as Policies: Language Model Programs for Embodied Control” at Google were showing what I thought were ground-breaking advancements in embodied AI with LLMs, and in a shocking double-punch META released the first LLaMa model at the end of February and barely 2 weeks later authors at Stanford released Alpaca-7B, an instruction-tuned version of LLaMA, that showed how cheap instruction-tuning was and effectively showed to academics all over the world that they could do hands-on research on these models.

This was not lost on me, and I started catching up with the research on LLMs, while dealing with my successful re-submission in half-April 2023. Another paper released in May that had a big effect on me was “Voyager: An Open-Ended Embodied Agent with Large Language Models” from Guanzhi Wang et al. mostly done at NVIDIA, which convinced me that LLM agents were a very promising research direction. In my mind I called them “LLM-based algorithms” and I thought that they were being so successful that soon the hot questions would be what was the optimal design of such algorithms and whether LLMs themselves could write them. So, in June I set out to explore how one could set up a benchmark for that. This turned out to be hard and fuzzy to define concretely, thus I pivoted towards exploring the ability of one LLM to improve the performance of another via prompting. I picked the domain of coding, probably because it had two convinient properties: it is natively understandable for LLMs and it has an automated and precise way to establish if a program is correct.

Research idea

Coding LLMs were tested by giving as input an instruction such as “Complete the code for the following function” and, in the case of Python, the header and docstring of the function to be completed. The LLM would then produce the continuation and this, together with the part given as input, would be executed with some test inputs, to check whether the function’s outputs were equal to the expected test outputs.

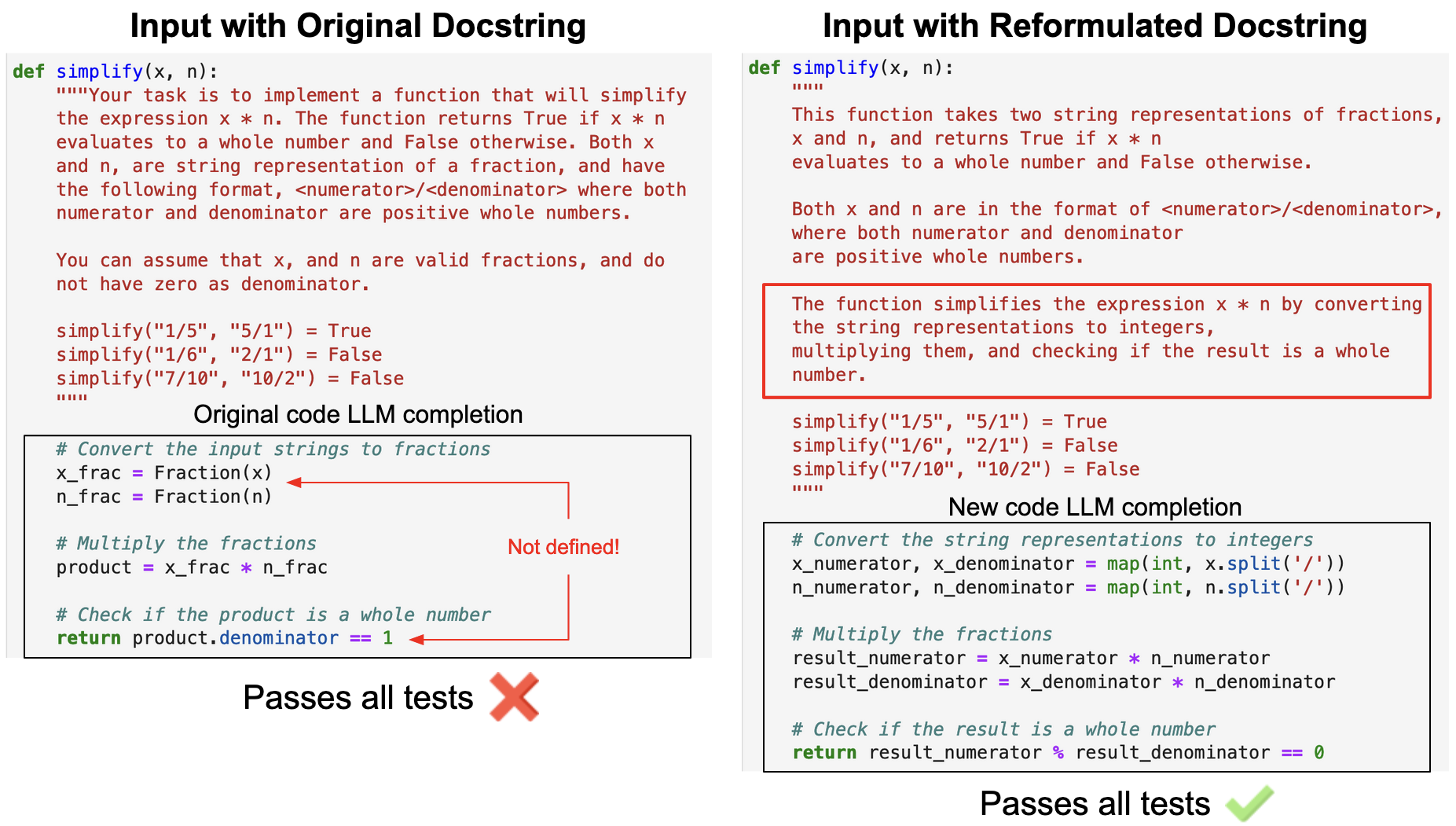

My thinking was that the docstring carried a lot of information about the task to be completed, yet nobody had tried to see if there was an optimal way of writing the docstring that would elicit an optimal response from a model. More than that, as models kept on coming out at breakneck speed, I wanted to see if there was a way of writing docstrings that would be optimal for any given model that was sufficiently proficient at code. In a way, I was looking for quirks in code LLMs like “Let’s think step-by-step” was for reaosning or “8k, tending on artstation” was for text-to-image generation. Here’s a motivating example from the paper:

How to do that? By reformulating the existing docstring of an input program to be completed! One could optimize the reformulation process by maximizing the likelihood that the decoded program would be successful. My idea was to try and discover emergent patterns by basically sampling multiple reformulations with an LLM and learning from the best of them.

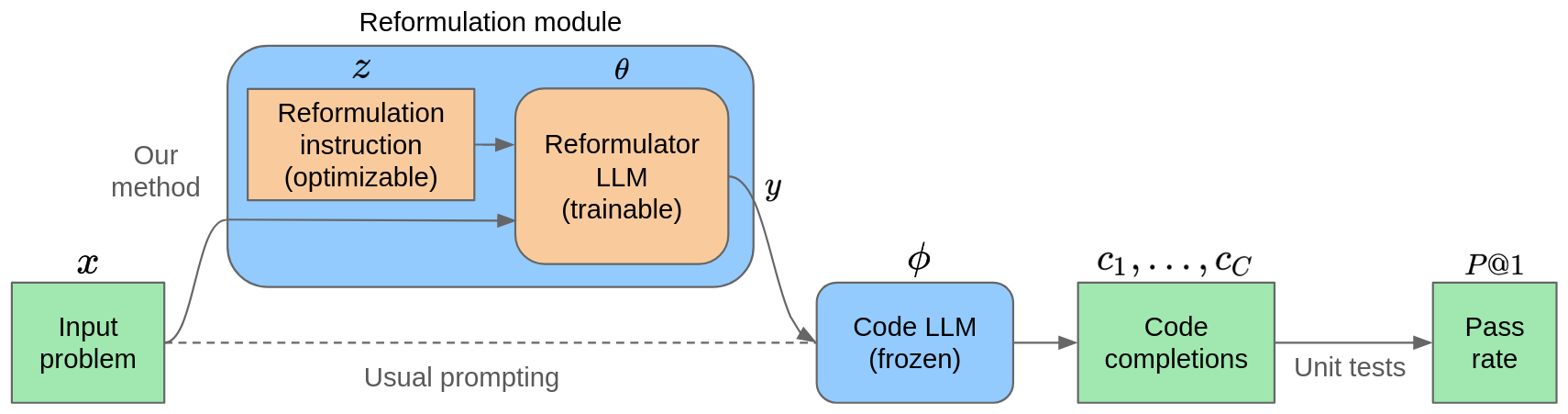

The setup was the following: I would have two LLMs, a “reformulator” LLM and a code LLM, as shown in the figure below:

The reformulator would receive an instruction that would specify how to reformulate and the header and docstring of the function, and then it would output the reformulated dosctring (or multiple of them during training). The code LLM, which I kept frozen during training, would take the reformulated docstring and decode the body of the function, which would then be evaluated against the unit tests.

I had two main methods of optimization in mind:

- Use supervised fine-tuning over the best reformulation for every prompt to train the reformulator;

- Optimize the reformulation instruction using Optimization via PROmpting (ORPO), a black-box optimization technique from a Google DeepMind paper, that uses in-context abilities of LLMs to optimize a problem that receives a string as input.

As a third method, I also tried to combine them.

The initial results were not great: the optimization was barely working, in the sense that the downstream performance was not really improving at all, and I was using such a small dataset (HumanEval) that I didn’t even have train/validation/test splits (I am still ashamed of that). Overall, I took a good look at my work and my situation, and decided that I didn’t want to spend too much time on this, as it felt like a rabbit hole, so I started converging toward a comprehensive analysis of the potential and shortcomings of the approach.

So, what I ended up showing was that there were upper and lower bounds on the influence of a docstring on the downstream task, with the (experimental) extremes being respectively having the ground-truth solution copy-pasted inside the docstring and having no docstring at all. Furthermore, I discussed the limitations of the approach:

- Exploring the reformulation space

- Learning from a noisy feedback signal

I also had ablations with GPT-4 in certain places to show that my negative results were not due to the lack of a powerful model backbone for the reformulation part. I submitted the work to the Student Research Workshop of EACL 2024, as I felt that I had mostly negative results in my hands and I didn’t feel confident at aiming at a top-tier main track publication, and got it accepted.

Looking back

This time looking back I see lots of things I did right and much more research maturity from my side:

- Good intuition about the optimization paradigm: using rewards and lots of compute to learn without demostrations is a very strong paradigm. I was inspired by AlphaZero and how the model would learn by imitating the outputs of its own Monte-Carlo Tree Search, which in turn would improve the search itself in a virtuous loop. This has now become hot again as a topic, with the raise of Reasoning Language Models such as OpenAI’s o1 and o3 models, and the release of DeepSeek-R1.

- Having an interesting use-case in mind: a universal “improver” of code prompts to LLMs (even if that didn’t happen in the end) that could be useful to everyone dealing with code LMs.

- Wrapping up the work as soon as I became aware of some fundamental shortcomings of the approach, that made me disenchanted with the original idea. This gave me time to invest myself in a better idea later on, wiser of this experience.

- I successfully pivoted my research into Large Language Models coming from model-based RL, gaining extremely valuable experience in the hottest topic in the field with the excuse of this work.

What I should have known better:

- Prompt optimization without a differentiable objective (e.g. by using only rewards to rank different reformulation samples) is a very hard problem with little to no guarantees of success.

- Relying on emergent behaviours to magically solve your problem without either extreme scale (in terms of data, model parameters and compute) or strong exploration biases is a losing bet. I overestimated the creativity and diversity of the reformulations that an LLM could produce (even the ablation with GPT-4 as reformulator didn’t show any benefit!) and the quality and sensitivity to details of the open-source code LLMs I was using.

But what made me lose faith in the project was a simpler realization: the only way in which using a reformulator LLM to improve a code LLM made sense was if the reformulator could boost the performance of a code LLM more capable than the reformulator itself. Otherwise, one would be better off by just using the reformulator as the code LLM itself and avoid an extra LLM call. However, how could a weaker LLM improve the performance of a stronger one, if not with cheap tricks?

I had evidence in my experiments that adding hints about the solution in the docstring boosted performance significantly, but to do that, one needed to have access to the solution itself (or, be able to solve the problem independently), which would make the approach useless. So the only remaining hope was to find the equivalent of “Let’s think step-by-step” for code LLMs, but it didn’t make sense to have that within the docstring and my own hand attempts at docstring reformulation weren’t very successful.

So maybe the last question of this post is: if I were to go back in time with the knowledge of the time and just thought harder about what I just said above, what I would have picked as research topic?

I wish I asked more explicitly the question “What does it take to crack really hard problems that require creative exploration with LLMs?”, picked a coding benchmark and trained with RL-like methods, while experimenting with techniques to elicit a diverse set of strategies in tackling the problem. In a way, this would still be very relevant and hot topic today, so it would have been a great shot to try regardless of the results.