About me

Welcome to my personal website!

Reader: Model-based language-instructed reinforcement learning

This post is the first of a series that looks back at my works during the PhD, to reflect on what I wanted to do, the background story of the paper, what was promising, what were the biggest limitations of the project and overall what I learned.

Paper link: Reader: Model-based language-instructed reinforcement learning

Background

I started this work in early 2021, roughly one month after the beginning of my PhD, in what already feels like very different work. I was working fully remotely, as there was the Covid19 pandemic, RL was the cool thing to do, GPT-3 was out from half a year and there was no such a thing as an instruction-tuned LLM, let alone a compact, capable and open-source one that young researchers like me could even dream of using.

Unfortunately, my supervisor of the time, Alexander Ilin, pushed me to settle on a project quite quickly, without a proper vetting of the project’s promise or soundness. Also, I was coming from a Physics background, and I had only recently transitioned to Computer Science, with a Master that gave me the basics of Python, Machine Learning and Deep Learning, and a Master Thesis in Deep Reinforcement Learning under Aleander Ilin. So, while my theoretical understanding of Deep Learning and Reinforcement Learning was rather good, in retrospective I was having some serious gaps in my software engineering skills, which no doubt impacted the timeline of the project.

Anyway, we picked one paper that looked interesting: “RTFM: Generalising to Novel Environment Dynamics via Reading”, from Victor Zhong, Tim Rocktäschel, Edward Grefenstette, and decided to propose a model-based version of their model-free approach. In a nutshell, Read To Fight Monsters (RTFM), was a grid-world environment with 2 monsters, 2 items and one agent, and the goal of the agent was to kill the monster belonging to the target team for that episode. So far, trivial for basic RL agents. The catch was that at every episode lots of things were randomised, so that an agent that would base itself only on the symbolic observations of the grid wouldn’t be able to achieve more than 25% win rate. Instead, a manual containing all the relations needed to infer which monster was part of the target team and which item (weapon) could defeat it, was generated at each episode and given to the agent. So, the only way to solve the task optimally, is to learn to read the manual and use the information within it to pick the right item and fight the right monster.

Research idea

Let’s take a step back and see why that was a research line that was of interest to me and other people. RL agents clearly showed superhuman performance in very challenging tasks, such as Atari console games, Chess, Go, Starcraft, DOTA, etc. However, they had no generalization capabilities outside of the environment they were trained on, and possibly very different representations of the state of the RL environment than humans do (e.g., we think of objects, concepts, give names to both, are able to tranfer knowledge between tasks based on that, can recognise or “ground” words in observations). Therefore, language was to me and probably to many others, a promising way of generalising RL agents performance to new environments by providing them only with a language update of what changed from training to test time. The main idea was that generalisation comes from training on a large and diverse distribution of tasks, and that DL-based RL agents can “ground” (or cross-reference) language information to visual (or symbolic) observations by fusing the two representations and training on tasks that force the agents to leverage the language information, as was the case in the RTFM environment.

So why did we decide to do a Model-based RL agent? The short answer is because we hypothesized that such agents would be much more sample-efficient than the model-free counterpart. The task required roughly 5/6 logical hops cross-referencing written and symbolic information, and the model-free method proposed by Zhong et al. was taking a million steps to solve the task, plus a complicated curriculum learning procedure for making progress on the harder variants of the environment! That felt way too inefficient for this to achieve any real world generalisation abilities, so we set out to find a more efficient way of doing the same.

Now, that’s not a bad plan on the surface, yet it’s certainly not perfect, but more on that later.

Implementation

Since the environment had discrete actions, I started looking into MCTS and MuZero as promising model-based approaches. After being frustrated on the poor MuZero open-source replication attempts, I set out to code MCTS with policy and value networks from scratch and tried them out on a simplified version of the environment (static and always with the same manual). I played with all sort of variants of MCTS until I had some good degree of success on this and then moved out to the slightly more complex case, where the manual was always the same, but the monsters would move with stochastic patterns. MCTS needed to be extended to handle stochastic transitions, which was not-so-straightforward given the lack of literature on it, but I managed.

Until this stage, if I remember correctly, I had been relying on a copy of the true environment as a simulator for MCTS, rather than learning one with a neural network from the data. Finally the moment had come, and that’s when I encountered one of the hardest parts of the project. In order to construct a tree of actions and state transitions, the amount of possible state transitions needs to be finite, or the tree would always branch at the first state transition and be essentially useless. However, I wanted to model state transitions in the latent space, and not in the observation space, as that seemed a more general and scalable approach (I should really elaborate more on the argumentation behind this choice!). Thus, I needed to learn a discrete probability distribution in order to get only a finite amount of possible transitions, and for that, I needed to also learn some sort of discrete latent space.

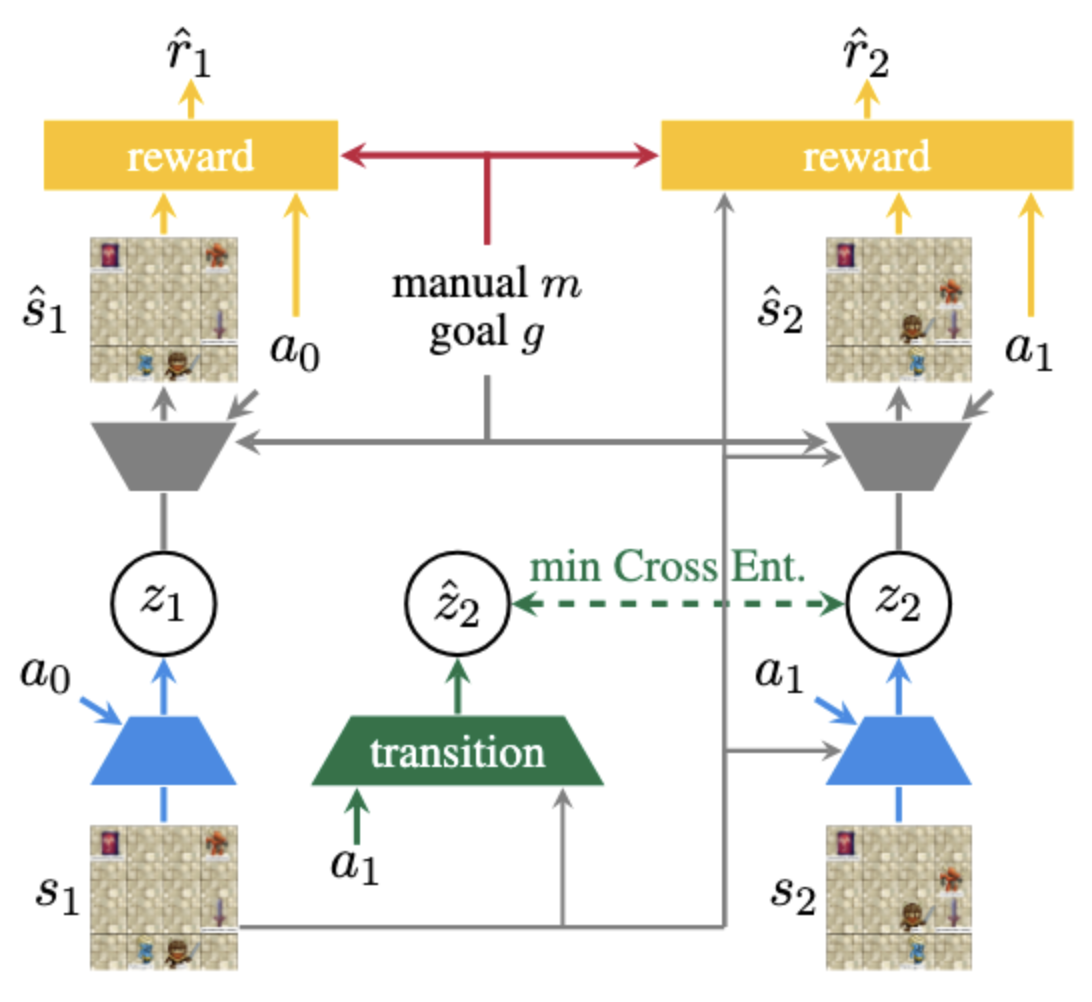

There were a couple of works doing something of the sort, DreamerV2 from Danijar Hafner et al. at Google Research/DeepMind in October 2020 and Vector Quantized Models for Planning from Sherjil Ozair et al., also from DeepMind, in June 2021. As a reference, I started working on this part roughly on September 2021. I tried the two avenues proposed in those works: Vector Quantization, and Discrete Latents learned with the Gumbel-softmax trick, and I guess that Vector Quantization was more stable. Slowly, the main architecture started to take shape, but somehow it took me all the way to June 2022 to get a satisfying performance from this Vector-Quantized-based Dynamics Model, which is depicted in the image below:

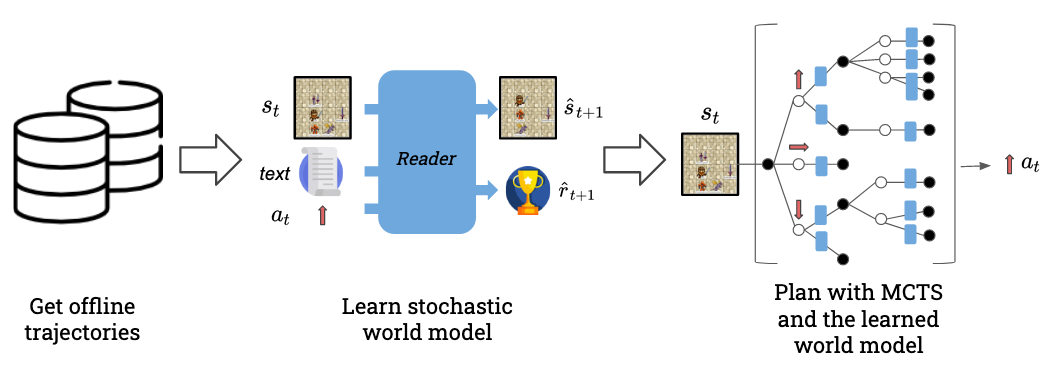

Then it came the last big challenge: learning to read the manual via RL. It turned out that the reward function had to encode all the reasoning, cross-referring the observations with the manual, and generalise at test time. I had zero NLP experience and lots of time pressure to wrap up the work by this stage. For whatever reason, a vanilla transformer would not learn well the reward function given the amount of data that I was considering, so after all sorts of trials, I ended up repurposing the original policy and value network proposed by Zhong et. al in RTFM to a reward function and that sort of did the trick. The high-level overview of the work ended up being the following:

The results were still not great, in the sense that while the sample efficiency was way better (100x or more), our method was not making enough progress on the hardest tasks. We submitted a first version to ACL in December 2022 and then a revised version with more refined experiments to EMNLP in April 2023, which finally got accepted.

Looking back

Spending more than 2 years on a single work that I barely had time to choose was very taxing and it greatly impacted my mental health and the overall experience of the PhD. After finishing it, I promised myself that I would never put myself in the same situation again. I learned the importance of taking the time it takes to choose a project, of being rigorous and systematic in planning experiments so not to get lost, of not giving anything for granted until I test it, setting a timeline for a project and openly discussing a plan B before the only options are “get the experiments to work” or “drop the project and fail the PhD”.

On the level of research ideas, I think it’s clear to me that sample-efficient deep learning so far remains a chimera and the paradigm of solving one toy problem at the time with the hope of scaling up a method that had been heavily tailored to solve the specific problem is also not the right one in this case, as in RL the different environments are so different. Relying on foundation models for generalisation seems to be the best bet we have today, but this wasn’t at all obvious to me and moreover a part of me wanted to believe that a clever RL procedure could discover human-like concepts totally from scratch, and that seemed much more elegant than collecting human demonstrations for every single thing we want to learn.

So how could I have better used my two years of research by picking a better idea based on the evidence that was available to me at the time?

- Internalise the Bitter Lesson from Richard Sutton and kill any idea that relies on things that are non-trivial to scale up,

- Take much more time to look around and read what was happening in other fields (even if my grant was in Deep RL, both Computer Vision and Natural Language Processing provide extremely valuable perspectives to the field),

- Make sure that whatever project you embark on, at least it tries to answer to a clear research question that won’t be obsolete by the time the project is done.

That said, I cannot think of any precise high-impact project I could have taken on, as I lacked the research knowledge, technical experience, infrastructure and collaboration network to do anything of the sort. But if I had, maybe one question that I would have liked to address is “Under which conditions is model-based reinforcement learning better than model-free RL?” with obvious follow-up “Should we forget about model-based reinforcement learning, or double down on it?”. Of course, these are not questions that can be definitely be answered by a single work, but maybe precisely for that reason, any work taking a step towards an answer to them might have long-lasting effects.