About me

Welcome to my personal website!

In-Context Symbolic Regression: Leveraging Large Language Models for Function Discovery

This post is the third of a series that looks back at my works during the PhD, to reflect on what I wanted to do, the background story of the paper, what was promising, what were the biggest limitations of the project and overall what I learned.

Paper link: In-Context Symbolic Regression: Leveraging Large Language Models for Function Discovery

Background

Back in September 2023 my colleague Katsiaryna Haitsiukevich (Kate) asked me if I was interested in co-supervising some master’s students for a small research project involving LLMs and their possible application to the discovery of physics and math equations from data. Since that didn’t sound like too much work, the topic was interesting enough for me and she’s a collegue I get along well, I accepted. The proposal we published was mentioning a somewhat vague research direction along the lines of: “In this project, we will study different approaches on how LLMs can be utilized in the context of physical system modelling, such as finding the analytic form and coefficients of the differential equation that models certain data points.” We got two applicants and accepted both for two different projects, and this is the story of the project that got published. The student, Matteo Merler, was taking a seminar course on LLMs that I was the main organiser of, and I knew from there that he was a good student. What I didn’t imagine was that he would become my main collaborator for the following two years, and I am so grateful of this project for setting all that in motion.

Research Idea

Our starting point and inspiration was a paper from Google DeepMind called “Large Language Models as Optimizers”, where the researchers showed how an LLM could, among other things, find the coefficients of linear equations given some data. The method, called Optimization by Prompting (OPRO), would prompt the LLM with an optimization task and a series of previous attempts together with how well they scored on the problem (e.g., by reporting the mean squared error of the fit), ranked in ascending order. This would be also referred to as an optimization trajectory. The LLM would then use its pattern-matching abilities to guess a solution, while taking into account the pattern formed by the previous attempts.

We discussed how we could apply this to the problem of equation discovery. Kate was motivated by the idea of discovering differential equations, as she had some experience in how cumbersome the process is. However, as it was hard to fully wrap our heads around which setup was needed for that, we opted to focus on simpler one-dimensional equations.

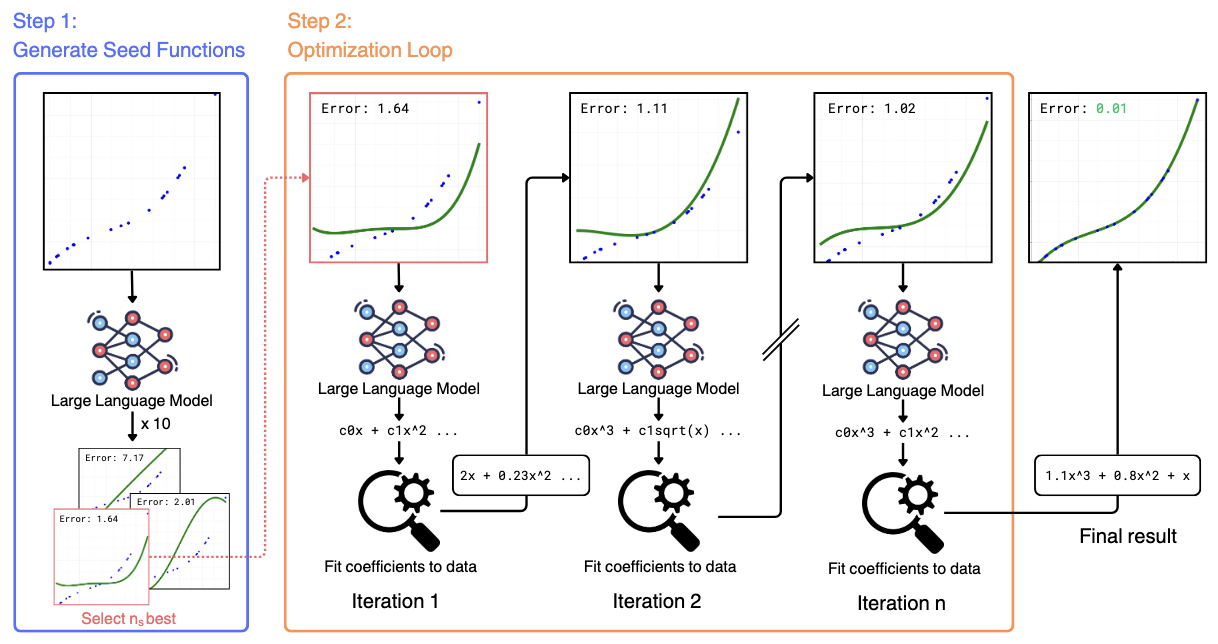

Initially we just decided to predict the full equation, coefficients included, as one concern was that not specifying the coefficients of an equation could lead to unstable fits. However, we didn’t observe such instabilities ourselves and changed the method to predict only the skeleton of the equation (e.g., $y = c_0 + c_1 x + c_2 x^2$). Following the LLM prediction, we would parse the equation and optimize the coefficients on the training datapoints using Non-linear Least Squares.

One problem was how to score a proposed function: we imagined that LLMs would find it easier to see patterns in the solutions if their scores would be between 0 and 1 or some similar range. After some trials, we settled for the normalised mean squared error (NMSE): \(NMSE(f|D) = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^N (y_i - f(x_i))^2}{\sum_{i=1}^N y_i^2 + \epsilon} ,\) where $\epsilon$ is a small regularising constant. While this is not between 0 and 1 strictly speaking, as the proposed function $\hat{f}$ approaches the ground-truth function $f$, in practice we found the metric to be well-behaved.

We then focused on removing the dependence of the optimization process of the hand-picked seed functions that we would include in the LLM prompt to get the optimization process started. To do that, we just wrote a generic prompt asking the LLM to generate “a set of functions that are as diverse as possible, so that they can serve as starting points for further optimization”, given a list of points observed.

This gave us the first draft of the method, that you can see in the figure below.

Ideas that didn’t work or we didn’t try

Before talking about the final details of the method and the results we got, I’d like to spend a few lines on some ideas that looked promising but didn’t work out, or we never tried due to time constraints.

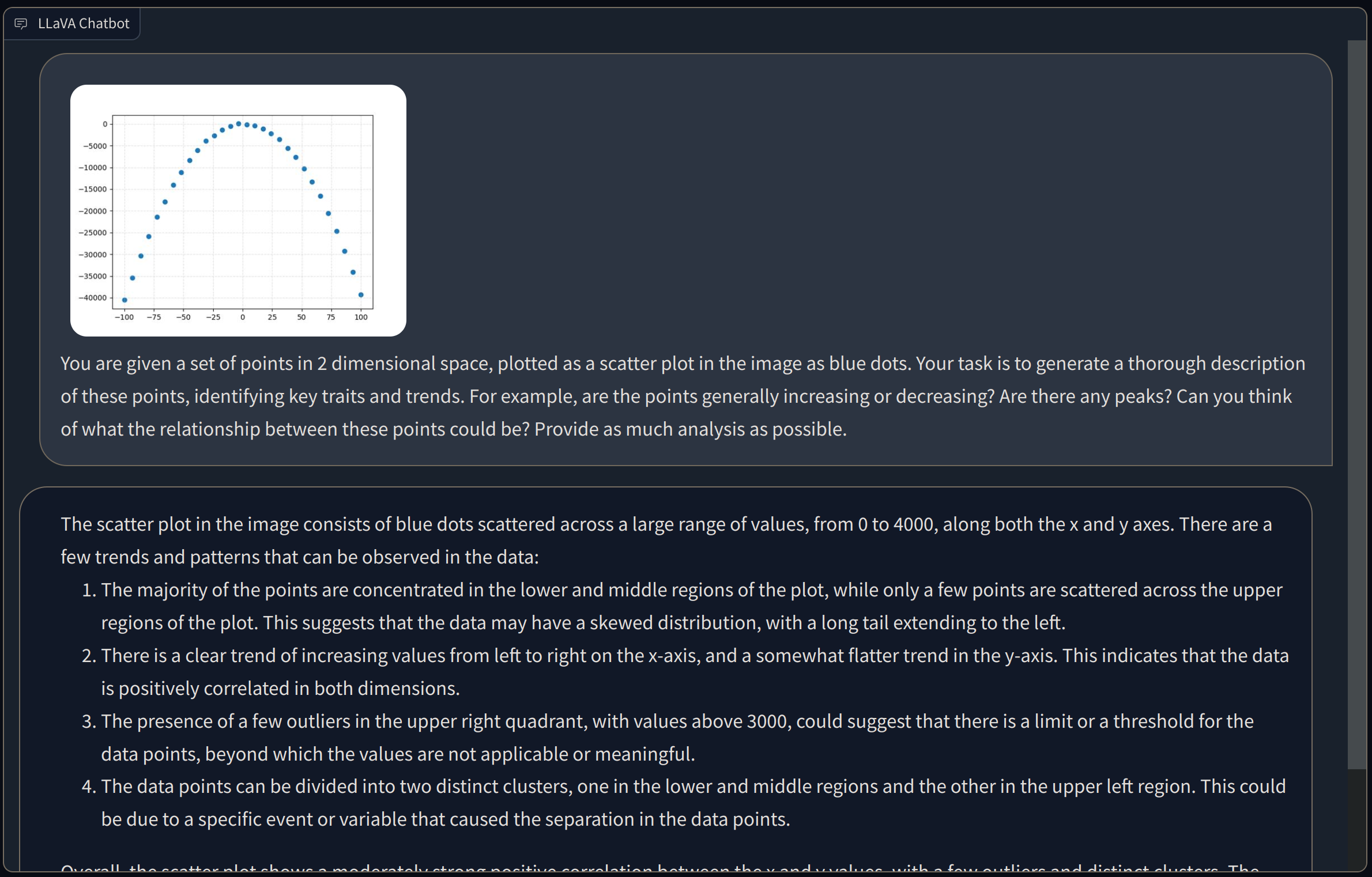

The first, which I personally liked a lot and pushed for, was to rely on image plots to enhance the quality of the proposed equations. The motivation was simple: as humans, many times, especially for low-dimensional data, we make sense of them by plotting them and inspecting them visually. What if we did the same with a Vision-Language Model? This was the moment when as a researcher you really get to appreciate the strangeness of the models and the pace of progress in AI: our initial experiments comparing text-only LLaMA2-7B vs vision-and-text LLaVa-1.5-7B showed a slight edge of the vision-and-text approach. However, the VLM had absolutely no clue of what was in the image if asked to describe it, as shown in the example below:

Finally, new versions of LLaMA (LLaMA-3) and LLaVa (LLaVa-NEXT) were released and LLaMA-3-8B slightly surpassed LLaVa-NEXT-34B, closing our exploration chapter of VLMs for good. Basing ourselves on text-only meant that the method could in principle handle data of any dimensionality, whereas with plots we could only represent 1-d equations in xy plots.

Some other ideas that we discussed, but never came around trying, were to enhance the proposal process of the equations, going beyond the implicit optimization performed via pattern-matching with the OPRO prompting. For example, we discussed having a critic LLM pointing out some shortcomings of current equations proposals, and incorporating that critique into the prompt for better proposals. We thought of either training a critic with some synthetic data over which we knew some privileged information to generate the critiques, or distilling critiques from a better model. However, I guess the idea of the critic was somehow linked to the vision approach and we ended up abandoning this route and focused on wrapping up the main experiments instead.

Final details and results

One final observation that we made (and were not the only ones) was that previous symbolic regression (SR) methods, based on genetic programming, search or RL, had the tendency to stacking and nesting a lot of terms in the equations found, resulting in much more complex expression than the ground trtuh. Inspired by “Transformer-based Planning for Symbolic Regression”, we added a term to the fit score to penalise complexity in equations, thus introducing an explicit trade-off between fit performance and complexity. We measured complexity as the amount of nodes in the expression tree (e.g., $sin(3x+2)$ would have 3 nodes, $sin()$, $*$ and $+$). For the penalty term itself, we used $\lambda \exp(- C(f)/L)$, where $\lambda$ is a hyper-parameter of the method (higher values increase the regularization) and $L=30$ is a constant we hand-picked. The penalty is to be minimised together with the normalised MSE (we did that in a more involved way, but it doesn’t change much in the end).

We tested our method, denoted as In-Context Symbolic Regression (ICSR), against a wide range of baselines in 4 common benchmarks in SR, all containing 1d and 2d equations. ICSR matched or outperformed all SR baselines, while producing simpler expressions that more closely resemble the complexity of theground truth equations and result in better out of distribution performance. We also got slightly better out-of-distribution performance, but in all fairness the benchmarks were all very saturated, with the best methods all reaching 0.999 out of 1 in many regression problems.

Looking back

This research work was certainly a good outcome for the time and effort we put in and a small but significant contribution in one topic that we were not familiar with.

I guess that in terms of what this paper could have been and what we could have done better, I would take inspiration from the following work, LLM-SR: Scientific Equation Discovery via Programming with Large Language Models, initially published on ArXiv in the same days of ours. LLM-SR went on to be accepted as an oral at ICLR 2025, whereas we got our work published as a workshop paper at ACL 2024.

Briefly, the bits I like from LLM-SR that we didn’t consider are the following:

- Working on more realistic equation discovery scenarios, such as on datasets coming from physics, biology or materials science.

- Moving from a symbolic regression scenario where you have generic datapoints in N dimensions, to a scenario where each of the N dimensions has a meaning, which is described in natural language to the LLM.

- Asking the LLM to output Python programs, rather than directly mathematical equations.

Point 1 is actually very complicated to do well, if you don’t have a collaborator in one of those fields that can give you the right pointers. Same for point 2, if you don’t have novel equations or the equations are too simple, the LLM is just going to zero-shot them, so you cannot convincigly do point 2 without point 1 (not until someone open-sources such a benchmark).

Point 3, while in practice it has the same expressive power of writing directly mathematical equations, synergises really well with having meaningful semantic names for the input variables (point 2), and probably helps the model forming some sort of Chain-of-Thought.

In terms of how the actual optimization is done, I think our promting strategy and scoring function was probably more advanced, while we could have explored with some sort of “experience manager” to increase the diversity of the solutions. The authors of LLM-SR used “islands” of solutions, i.e. separate clusters from which to sample past solutions as in-context examples. I won’t go into details, but it’s a quite common strategy in evolutionary algorithms.

More in general, I see that this line of research can be applied to a wider set of problems, as Google DeepMind has been doing with works like Mathematical discoveries from program search with large language models (applied to extreme combinatorics for the discovery of new algorithms), Discovering Symbolic Cognitive Models from Human and Animal Behavior (applied to discovery of analytical cognitive behavior models) and AlphaEvolve (general-purpose algorithm discovery and optimization).

In conclusion, symbolic regression is an area that has many connections with bigger topics, such as generic black-box optimization when the solution space is made of analytical expressions. Exploring the limits of LLM-based methods in this field remains an open challenge and I am glad of having gained some first-hand insights and experience in it. I am quite confident that there is still a lot of progress to be made and I am quite excited to follow it and let it inspire my view of what AI can be used for.